Spinning Space Stations That Tear Themselves Apart

A rotating space station may be built to slowly pull itself apart, trading structural strain and maintenance for artificial gravity that keeps human bodies closer to Earth norms.

A rotating space station may be built to slowly pull itself apart, trading structural strain and maintenance for artificial gravity that keeps human bodies closer to Earth norms.

Medieval stained-glass windows, built for religious storytelling, unintentionally functioned as early optical laboratories, experimenting with wavelength filtering, light scattering, and visual perception long before formal optics.

Many of the strictest dress codes come from offices and schools, which use clothing as low‑cost social control, outsourcing discipline and signaling power without explicit rules.

A beagle created as comic relief evolved into a benchmark for studying parasocial bonds, shifting empathy and attachment research toward fictional animals.

Common pantry foods like processed meats, refined carbs, and seed‑oil snacks accelerate arterial aging years ahead of your actual birthday.

The slapstick chaos of Tom and Jerry hides a precise visual language that modern UX designers mine for timing, clarity, and emotion without a single spoken word.

Fairy-tale cottages outperform many luxury hotels because they plug directly into the brain’s story circuitry, turning every stay into a narrative rather than a neutral transaction.

Replacing all drinking water with tea can strain kidneys, alter mineral and fluid balance, irritate the gut, and disrupt sleep, turning a healthy drink into a slow drain on systemic resilience.

Explores the physics and biology that make real humans unable to survive the extreme impacts, falls, and energy blasts routinely shrugged off by animated superheroes.

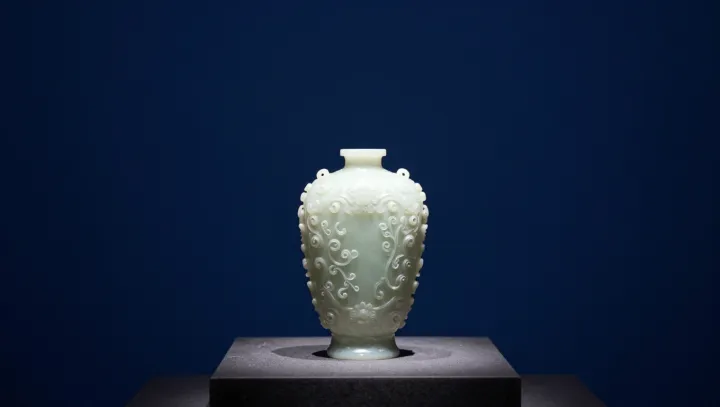

The winter‑blooming plum blossom rose to the top of Chinese floral rankings because its biology and timing matched ideals of moral resilience and cultured restraint.

Minimalist looks with one neon accent feel high fashion because they reduce cognitive load, heighten contrast, and trigger reward circuits for efficient visual processing.