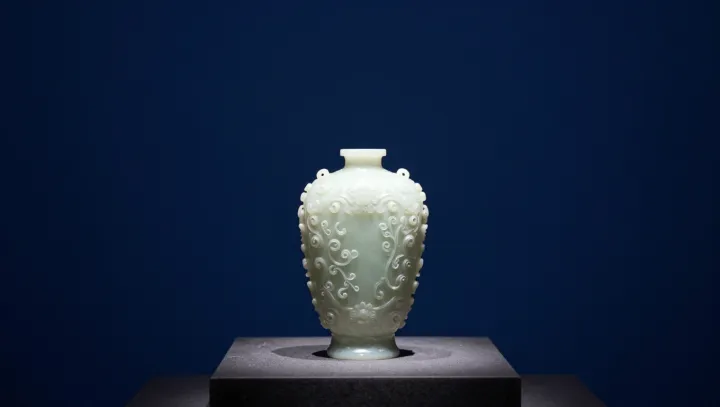

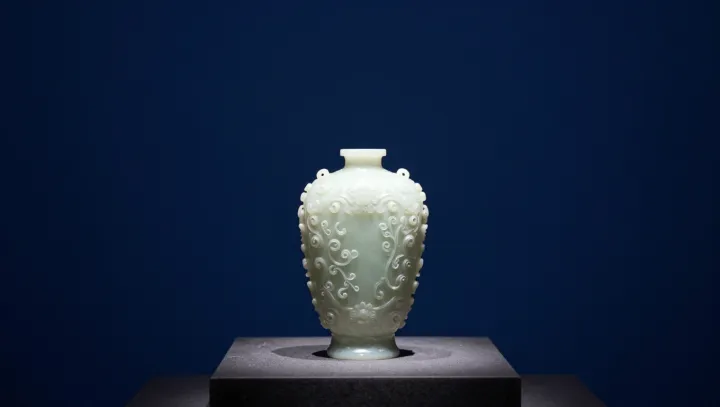

Plum Blossom: The First Flower of Winter

The winter‑blooming plum blossom rose to the top of Chinese floral rankings because its biology and timing matched ideals of moral resilience and cultured restraint.

The winter‑blooming plum blossom rose to the top of Chinese floral rankings because its biology and timing matched ideals of moral resilience and cultured restraint.

Captain America looks superhuman, but biomechanics and physiology show he is closer to a perfectly tuned Olympic decathlete than to a being that breaks human biological limits.

A mostly wordless children’s film uses visual storytelling and character design to explore loneliness, consumerism, and ecological collapse with more nuance than many prestige sci-fi dramas.

A once-dismissed kids’ cartoon quietly mapped out facial recognition, algorithmic politics, and platform power long before white papers, revealing how pop culture can surface weak signals of future systems.

Medieval stained-glass windows, built for religious storytelling, unintentionally functioned as early optical laboratories, experimenting with wavelength filtering, light scattering, and visual perception long before formal optics.

Viewed from Tokyo Skytree, Mount Fuji appears sharper in winter because colder, drier, denser air changes humidity, aerosol load and Rayleigh scattering, cleaning up the long sightline.

Snow machines turn liquid water into vast fields of unique snowflakes by tuning temperature, pressure, droplet size, and ice nuclei to control crystal growth in mid‑air.

A skyscraper clock keeps long‑term accuracy by locking a quartz‑controlled timebase to radio time codes from national standards, eliminating manual winding.

Olympic sailing teams exploit fluid dynamics, angle to the breeze and apparent wind to drive foils and sails so efficiently that boats can exceed true wind speed on specific courses.

Japan’s Mount Fuji, a national symbol, is largely owned by a private religious organization that leases land to public authorities, shaping park management and visitor access.

Ultra-light grey interiors look expensive because they exploit contrast perception, visual entropy, and social signaling, making spaces feel calm, precise and resource-rich to the human eye.