How Astronomers Map Hellish Alien Worlds

Astronomers use transit dips, stellar wobbles, and thermal spectra to infer exoplanet atmospheres so extreme that glass rain and global lava seas are now observational results, not fiction.

Astronomers use transit dips, stellar wobbles, and thermal spectra to infer exoplanet atmospheres so extreme that glass rain and global lava seas are now observational results, not fiction.

Chronic gender bias in childhood acts as a long-term neurobiological stressor, altering cortisol regulation and prefrontal-limbic connectivity in girls and leaving measurable traces in adult self-control and health.

Many young viewers say anime feels more real than live‑action because stylization strips away noise, magnifies emotion and social pressure, and aligns with their digitally fragmented inner lives.

Caribbean reefs can look vividly alive even when much of what you see is dead coral skeleton, because living polyps, algae, fish and microbes occupy and color these mineral frameworks.

Freezing water on a plate can grow branching ice flowers whose patterns obey the same diffusion laws and fractal geometry that govern snowflakes and lab crystal growth.

Replacing all drinking water with tea can strain kidneys, alter mineral and fluid balance, irritate the gut, and disrupt sleep, turning a healthy drink into a slow drain on systemic resilience.

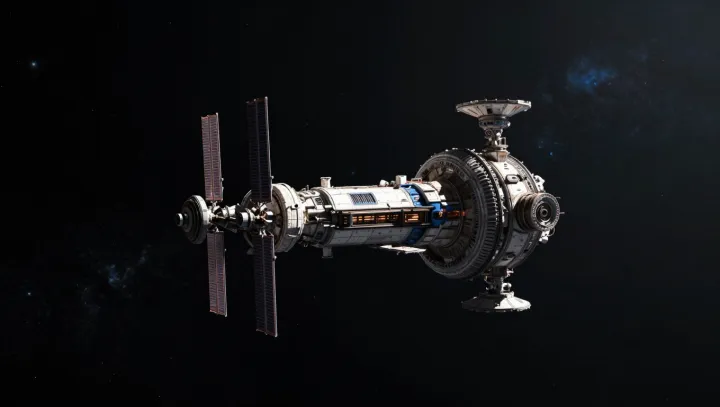

Space stations function as weightless laboratories where microgravity exposes hidden rules in fluid dynamics, biology and materials science, far beyond the idea of orbiting hotels.

An Akhal‑Teke can legally cost more than a Ferrari because of extreme genetic rarity, metallic hair microstructure, and a tightly controlled desert‑bred performance bloodline economy.

High fashion trends now shift at scroll speed as Instagram compresses a year’s worth of visual variety into a single minute of outfits.

Digestive research indicates that drinking milk on an empty stomach is generally safe for healthy adults, with discomfort linked mainly to lactose intolerance rather than any blanket medical ban.

The traditional Chinese ideal of subtle, layered beauty aligns with how the visual cortex and autonomic nervous system sustain attention and emotional calm.