Why Ships Mix Submarine Hulls And Skyscraper Tops

Naval architects design a ship’s hull like a submarine to manage hydrostatics and wave loads, while treating the superstructure like a skyscraper governed by wind and gravity-driven vibrations.

Naval architects design a ship’s hull like a submarine to manage hydrostatics and wave loads, while treating the superstructure like a skyscraper governed by wind and gravity-driven vibrations.

Quiet animated characters rely on implicit cues, activating social cognition and mirror systems that reshape moral circuitry more effectively than explicit lectures.

Belgium appears as one of Europe’s brightest zones from space because of ultra‑dense road lighting, continuous urban sprawl and planning choices that keep artificial illumination switched on across the map.

Modern supercars keep all four wheels gripping on ice by measuring slip in real time and vectoring torque, brake force and gear ratios through electronic stability and traction systems.

Two U.S. campuses with modest rankings have become high‑end choices for international students by prioritizing mental health, residential comfort and everyday usability over brand prestige.

Thunderstorms can launch upward lightning called gigantic jets and sprites, powered by electric fields that punch through the upper atmosphere toward space.

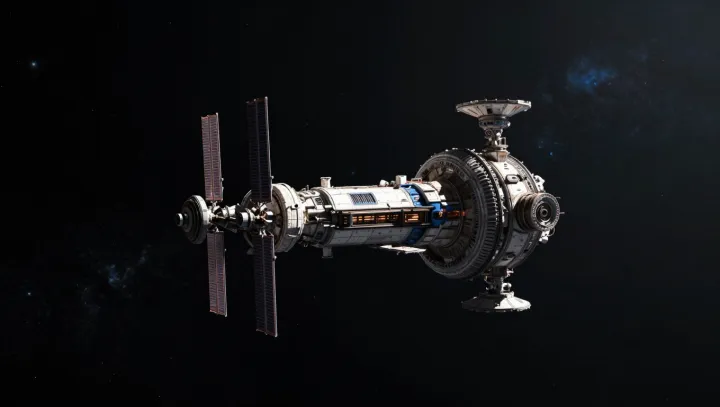

Space stations function as weightless laboratories where microgravity exposes hidden rules in fluid dynamics, biology and materials science, far beyond the idea of orbiting hotels.

Research shows cats seek humans who respect their personal space and let them initiate contact, not the most demonstrative cat lover in the room.

Minimalism shifts from counting objects to cutting decision noise, freeing cognitive bandwidth and time for high-value focus every day.

Kiwifruit, often treated as a background fruit, quietly surpasses many trendy snacks in fiber, vitamin C, antioxidants, calorie density and cost efficiency.

Silent forest walks reduce amygdala threat signaling, free up prefrontal cortex capacity, and rebalance autonomic networks that support willpower and long‑term decision making.