How Supercars Grip Ice Like Dry Tarmac

Modern supercars keep all four wheels gripping on ice by measuring slip in real time and vectoring torque, brake force and gear ratios through electronic stability and traction systems.

Modern supercars keep all four wheels gripping on ice by measuring slip in real time and vectoring torque, brake force and gear ratios through electronic stability and traction systems.

A home fish tank can distort indoor humidity, strain electrical safety, alter indoor air chemistry and disrupt sleep physiology long before any visible stress appears in the fish.

The Mandalorian grounds dogfights and armor in credible physics, from inertia and thrust to material limits, often outdoing films that claim hard scientific realism.

Rural wealth is tilting toward data-driven farms, cold-chain logistics and e-commerce hubs, where margins scale with algorithms, networks and asset utilization rather than pure land yield.

A road‑legal McLaren Spider hits 62 mph in 2.9 seconds by synchronizing aerodynamics, tire friction and traction algorithms into a mechanical web that locks the car onto the asphalt.

Many canonical artworks embed visual jokes and coded symbols that worked like slow-burn memes, letting painters speak across class, censorship and time while keeping official decorum intact.

A side project screen‑printing a cartoon monkey on T‑shirts evolved into an independent lifestyle brand with lasting global equity, outliving the company that first acquired it.

Two wool jackets diverge wildly in price when human hours, controlled supply chains and engineered scarcity turn fabric into a financial asset and a status signal.

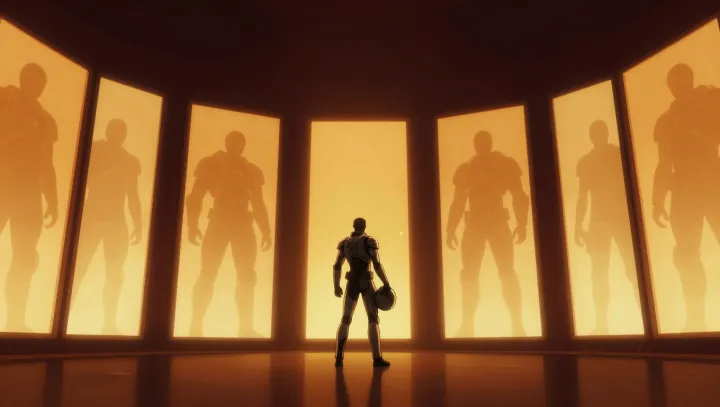

Iron Man’s flight fantasy runs into hard physics: current batteries lack the energy density and power-to-weight ratio to sustain a man-sized flying exoskeleton.

Renaissance artists used geometry, optics, and anatomy to simulate immersive virtual spaces on flat surfaces, turning painting into a proto–virtual reality system.

Moderate coffee and tea intake appears to reduce cardiovascular risk while supporting brain function, liver health, metabolism, mood and overall longevity through overlapping bioactive compounds.