When Painting Became Early Virtual Reality

Renaissance artists used geometry, optics, and anatomy to simulate immersive virtual spaces on flat surfaces, turning painting into a proto–virtual reality system.

Renaissance artists used geometry, optics, and anatomy to simulate immersive virtual spaces on flat surfaces, turning painting into a proto–virtual reality system.

Freezing water on a plate can grow branching ice flowers whose patterns obey the same diffusion laws and fractal geometry that govern snowflakes and lab crystal growth.

Elite servers trade raw speed for spin, margin of error and deception, using biomechanics and aerodynamics to win more points even when the serve is slower.

Belgium appears as one of Europe’s brightest zones from space because of ultra‑dense road lighting, continuous urban sprawl and planning choices that keep artificial illumination switched on across the map.

Two people read the same star‑filled sky in opposite romantic ways because their brains fuse raw sensory data with memory, prediction and social context to construct meaning.

Laughter and crying tap overlapping stress and reward circuits; when tension peaks and then feels safe, the brain flips the same arousal into social bonding and comic relief.

New labeling rules push snack packaging toward contract-style clarity. Three lines now shape real choices: serving size, added sugars, and front-of-pack nutrient flags.

A subtle sideways glance recruits peripheral vision, motion-sensitive pathways and the amygdala, enabling faster, more accurate threat detection than a straight, foveal stare.

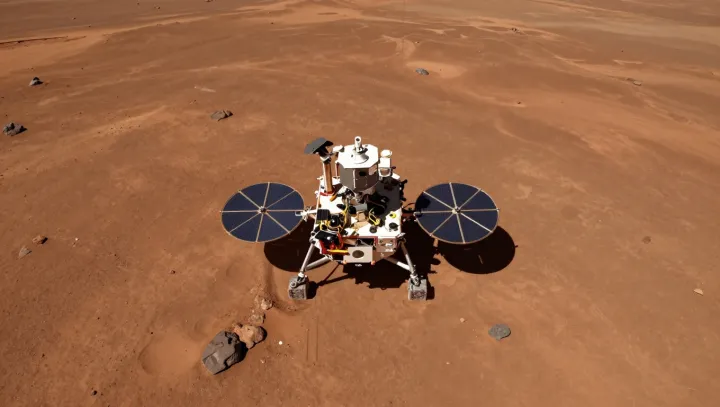

A stationary Mars rover built a multi-filter mosaic selfie to calibrate cameras, decode soil and ice composition, and refine climate models, turning vanity shots into hard planetary data.

Yogurt’s health halo hides wide gaps in sugar, processing and probiotic content, turning a simple dairy snack into a controlled experiment inside the gut.

A bone-inspired luxury jewelry collection uses anatomy, entropy and material science to turn fragile biology into a visual argument about evolution, permanence and metamorphosis.