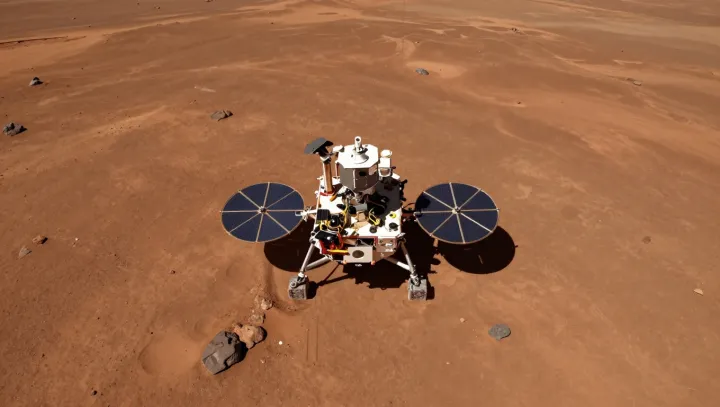

The Martian Rover That Built Its Own Selfie

A stationary Mars rover built a multi-filter mosaic selfie to calibrate cameras, decode soil and ice composition, and refine climate models, turning vanity shots into hard planetary data.

A stationary Mars rover built a multi-filter mosaic selfie to calibrate cameras, decode soil and ice composition, and refine climate models, turning vanity shots into hard planetary data.

Explores how AI illustrator Wukong converts loose mythic text prompts into stable, coherent visual universes using probabilistic sampling, latent space geometry and pixel-level consistency control.

The film reconstructs a fictional magazine with documentary rigor, mirroring real editorial workflows, aesthetics, and narrative structures of legacy print journalism.

Hand sketching remains central to car design because it compresses cognition, supports entropy-rich exploration, and shapes brand identity before 3D tools lock geometry.

Hyper‑realistic paintings can provoke stronger emotional and memory responses than matching photos because artists selectively amplify visual cues that align with the brain’s predictive coding and reward systems.

Research shows cats seek humans who respect their personal space and let them initiate contact, not the most demonstrative cat lover in the room.

Tea flavonoids can kill or slow cancer cells in controlled cell cultures, but metabolism, dose, and lifestyle noise dilute those effects in real life, so cancer protection is never guaranteed.

Black holes are not perfectly black. Quantum field theory near the event horizon predicts Hawking radiation, which drains their mass as entropy and information flow outward until the object vanishes.

A thin veil of mountaintop snow exists only because tectonic plates collide, fold and uplift rock, turning deep crustal violence into high, cold platforms for ice and weather.

Japan’s Mount Fuji, a national symbol, is largely owned by a private religious organization that leases land to public authorities, shaping park management and visitor access.

Tiny emoji work as fast semantic cues: they modulate reading speed, emotional valence and perceived politeness by hijacking prediction, attention and social norm circuits.