Why Trimming Spent Succulent Blooms Matters

Allowing a succulent to finish blooming and then removing the flower stalk redirects carbohydrates and water to storage tissues, boosting leaf thickness and long term plant health.

Allowing a succulent to finish blooming and then removing the flower stalk redirects carbohydrates and water to storage tissues, boosting leaf thickness and long term plant health.

Simple changes in cycling posture can redirect effort from legs to heart, core and balance system, turning one ride into distinct physiological workouts without new gear.

Renaissance painters embedded visual jokes in masterpieces by turning everyday objects into coded symbols that mocked, flirted or moralized behind a veneer of piety.

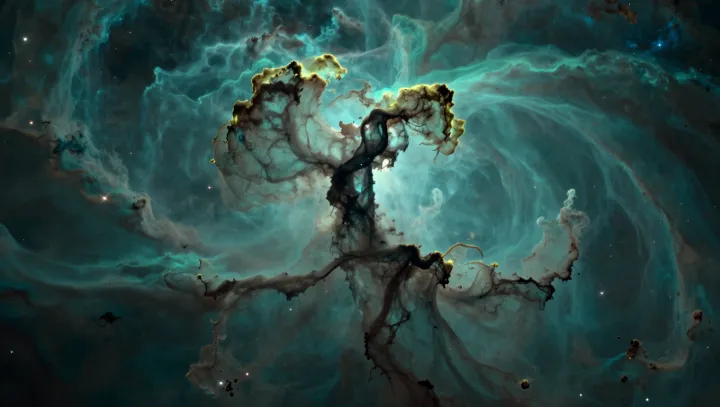

A rare astrophysical maser in an otherwise ordinary nebula revealed Doppler signatures of a hidden companion star that had evaded direct imaging.

Viewed from Tokyo Skytree, Mount Fuji appears sharper in winter because colder, drier, denser air changes humidity, aerosol load and Rayleigh scattering, cleaning up the long sightline.

Germany’s iconic timber-framed houses look romantic but emerged as a medieval engineering response to scarce stone, fire risk, and subtle seismic forces.

Romantic bonds trigger the same dopamine reward circuitry as addictive drugs, but oxytocin, prefrontal control and secure attachment convert short‑term spikes into long‑term emotional stability.

Explains how structural flexibility, tuned mass dampers, and aerodynamic design let skyscrapers sway more than a meter in strong winds without disturbing people inside.

Tracing how an early canvas experiment evolved into Monogram bags that operate as luxury signals, financial assets and rigorously engineered everyday tools.

The Ferrari Dino GT, sold as an entry‑level model, used mid‑engine packaging, lower polar moment of inertia and better weight distribution to outperform the brand’s front‑engine V12 grand tourers.

Most malformed strawberries are driven by genetics, temperature stress and pollination failures, not by excessive pesticide use, reshaping how consumers read visual signals on fruit.