Why Mount Fuji Sharpens in Tokyo’s Winter Sky

Viewed from Tokyo Skytree, Mount Fuji appears sharper in winter because colder, drier, denser air changes humidity, aerosol load and Rayleigh scattering, cleaning up the long sightline.

Viewed from Tokyo Skytree, Mount Fuji appears sharper in winter because colder, drier, denser air changes humidity, aerosol load and Rayleigh scattering, cleaning up the long sightline.

Tea flavonoids can kill or slow cancer cells in controlled cell cultures, but metabolism, dose, and lifestyle noise dilute those effects in real life, so cancer protection is never guaranteed.

PSG became a financial superpower through state‑backed capital, commercial leverage and brand strategy, yet structural flaws keep blocking a Champions League title.

Astronauts train underwater because neutral buoyancy lets engineers and crews rehearse orbital weightlessness, refine procedures, and manage physiological limits before real missions.

Even when the sea looks calm, small ripples act as a dynamic record of distant winds, tides and the combined gravitational pull of the Moon and Sun on Earth’s oceans.

Quiet lakeside settings reduce cognitive load and restore attention networks, often delivering deeper mental recovery than activity‑heavy wellness programs.

Nike moved from an early marathon shoe that contributed to injuries to a carbon-plated, foam-heavy racer so efficient that the global regulator rewrote footwear rules.

Honey shifted from ancient wound treatment to rigorously tested natural preservative, thanks to its low water activity, acidity, hydrogen peroxide and antimicrobial compounds.

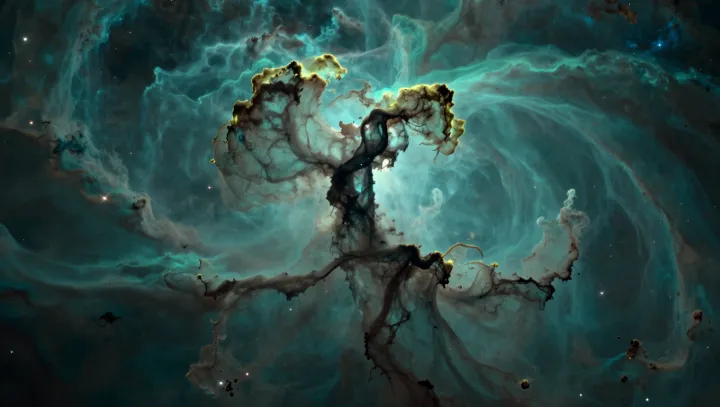

A rare astrophysical maser in an otherwise ordinary nebula revealed Doppler signatures of a hidden companion star that had evaded direct imaging.

Deadpool’s instant regeneration makes a sharp contrast with slow, tightly regulated human tissue repair, revealing why full organ or limb regrowth would break the rules that keep cancer in check.

Thunderstorms can launch upward lightning called gigantic jets and sprites, powered by electric fields that punch through the upper atmosphere toward space.