How One Egg Bridges Class, Cuisine, and Science

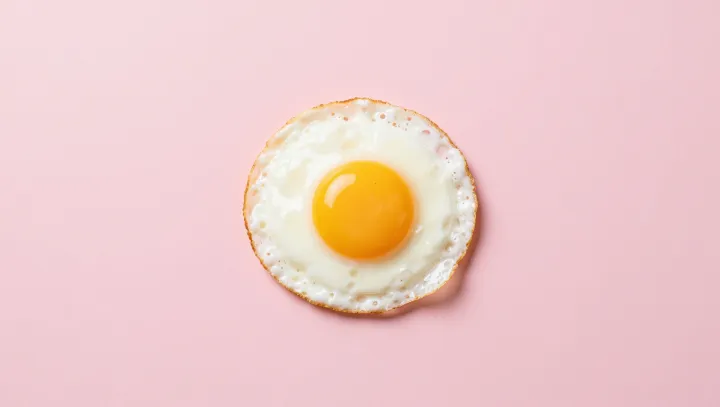

The chicken egg sits at the crossroads of poverty cuisine, Michelin innovation, and nutrition science, thanks to unique economics, chemistry, and amino acid geometry.

The chicken egg sits at the crossroads of poverty cuisine, Michelin innovation, and nutrition science, thanks to unique economics, chemistry, and amino acid geometry.

A mute parrot in Empresses In The Palace exposes how fear, not censorship alone, drives information control and erodes psychological safety inside any hierarchy.

Young drivers are shifting from traditional dream cars to compact, tech-heavy EVs, prioritizing software, connectivity, and total cost of use over raw power and luxury.

Astronomers restricted the word “planet” to preserve clarity and dynamical order as thousands of similar bodies were discovered in the solar system.

The slapstick chaos of Tom and Jerry hides a precise visual language that modern UX designers mine for timing, clarity, and emotion without a single spoken word.

Emotionally soft homes usually rest on tough conversations about boundaries, needs, and conflict, creating psychological safety through honesty rather than constant harmony.

Dragon docks with the ISS by fusing radar and optical sensors, running real-time orbital mechanics instead of GPS, and flying a sequence of precise, autonomous burns.

Alps in Europe, Japan, New Zealand, and North America share a name because people reuse familiar labels for similar landforms, exposing a cognitive shortcut in global place-naming.

Ultra-pricey ice cream is driven less by gold leaf and hype than by rare agricultural inputs, extreme labor intensity, and luxury-goods economics.

The real castle that inspired Snow White’s palace became an obsessive prestige project, draining its monarch’s finances, eroding political capital and hastening his removal from power.

An engineering breakdown of the extreme structural, metabolic, and respiratory redesigns a land mammal would need to survive and move at true ocean-floor pressure.