How Dragon Hits a Moving Target in Orbit

Dragon docks with the ISS by fusing radar and optical sensors, running real-time orbital mechanics instead of GPS, and flying a sequence of precise, autonomous burns.

Dragon docks with the ISS by fusing radar and optical sensors, running real-time orbital mechanics instead of GPS, and flying a sequence of precise, autonomous burns.

A mostly wordless children’s film uses visual storytelling and character design to explore loneliness, consumerism, and ecological collapse with more nuance than many prestige sci-fi dramas.

Pastoral landscapes that seem untouched are often tightly engineered systems, shaped by grazing regimes, hydrology control and species selection into stable, productive cultural ecosystems.

Neuroscientists report that strenuous mountain climbs can trigger neural and hormonal states similar to deep meditation or short sensory deprivation, producing a shared sense of mental clarity and reset.

The Kung Fu Panda franchise blends comedy and spectacle with authentic kung fu principles, translating Chinese martial philosophy into global pop culture without faking the physics of real combat.

Mars hosts a canyon system far larger than the Grand Canyon, carved by tectonic stress, volcanism, and ancient water, revealing a far more dynamic planetary past.

The Lancia Stratos fused a Ferrari V6, mid‑engine layout and purpose‑built packaging to reset the physics of rallying and dominate its era.

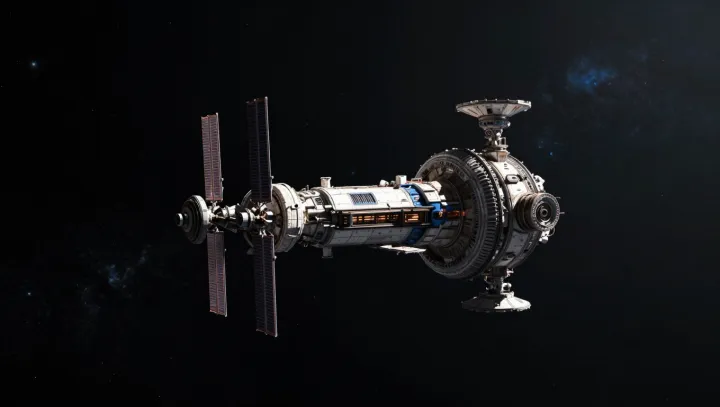

Space stations function as weightless laboratories where microgravity exposes hidden rules in fluid dynamics, biology and materials science, far beyond the idea of orbiting hotels.

Explores how AI illustrator Wukong converts loose mythic text prompts into stable, coherent visual universes using probabilistic sampling, latent space geometry and pixel-level consistency control.

Psychologists argue that slightly sub‑dream goals exploit marginal effects in motivation and perceived self‑efficacy, creating a repeatable loop of wins that compounds confidence.

A children’s racing cartoon turns lap times and pit stops into a subtle guide to burnout, ego management, and graceful aging that most self‑help manuals miss.