Why Butterflies Chase Useless White Scraps

Butterflies often chase white paper because their visual system keys on motion, shape and brightness, causing simple scraps to trigger mate‑seeking circuits.

Butterflies often chase white paper because their visual system keys on motion, shape and brightness, causing simple scraps to trigger mate‑seeking circuits.

A rare astrophysical maser in an otherwise ordinary nebula revealed Doppler signatures of a hidden companion star that had evaded direct imaging.

Emerging evidence suggests that cutting a single teaspoon of daily salt may lower blood pressure as much as a common hypertension pill by shifting renal sodium handling and vascular resistance.

Research shows cats seek humans who respect their personal space and let them initiate contact, not the most demonstrative cat lover in the room.

High fashion trends now shift at scroll speed as Instagram compresses a year’s worth of visual variety into a single minute of outfits.

Despite precise digital simulations, car design teams keep starting with pencil sketches because hand drawing drives fast iteration, creative exploration, and early constraint framing before CAD and CFD lock the geometry.

Physicists used general relativity, traversable wormhole equations and energy conditions to test whether Thor: The Dark World’s portals could exist, and found they demand exotic matter and violate known physics.

Digestive research indicates that drinking milk on an empty stomach is generally safe for healthy adults, with discomfort linked mainly to lactose intolerance rather than any blanket medical ban.

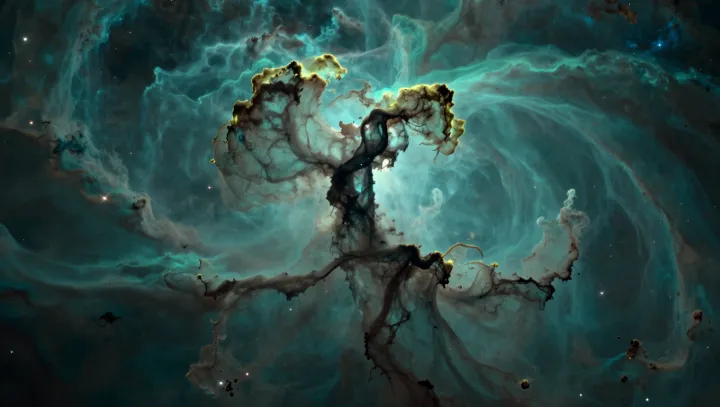

Explores how AI illustrator Wukong converts loose mythic text prompts into stable, coherent visual universes using probabilistic sampling, latent space geometry and pixel-level consistency control.

Professional buyers argue that two invisible layout rules, circulation clarity and functional zoning, shape spaciousness, calm and long-term livability more than cosmetic finishes.

Snow machines turn liquid water into vast fields of unique snowflakes by tuning temperature, pressure, droplet size, and ice nuclei to control crystal growth in mid‑air.