How Jaguar Hacked Le Mans Aerodynamics

The Jaguar D-type reached extreme speeds through meticulous analog aerodynamics, balancing drag reduction, stability, and cooling using wind tunnels and slide rules.

The Jaguar D-type reached extreme speeds through meticulous analog aerodynamics, balancing drag reduction, stability, and cooling using wind tunnels and slide rules.

Tiny changes in one corner of a room alter visual load, cognitive control, and reward cues, measurably shifting how often you notice distractions and how long you stay focused.

Traditional New Year rules work because they target habit loops and neuroplasticity, rewiring reward pathways exactly when you feel tempted to rely on luck.

Most malformed strawberries are driven by genetics, temperature stress and pollination failures, not by excessive pesticide use, reshaping how consumers read visual signals on fruit.

The Ferrari Dino GT, sold as an entry‑level model, used mid‑engine packaging, lower polar moment of inertia and better weight distribution to outperform the brand’s front‑engine V12 grand tourers.

The mantis shrimp, armed with raptorial appendages powered by elastic energy storage and cavitation, strikes prey so fast that only high‑speed, slow‑motion imaging can reveal its hunting behavior.

Meerkats use anatomical cooling tricks, behavioral timing and social rotation to withstand extreme desert heat while maintaining constant vigilance for predators.

A counterintuitive look at ski safety: thinner layers, slightly looser boots and slower early runs protect warmth, circulation and joint control better than over-tight gear and instant speed.

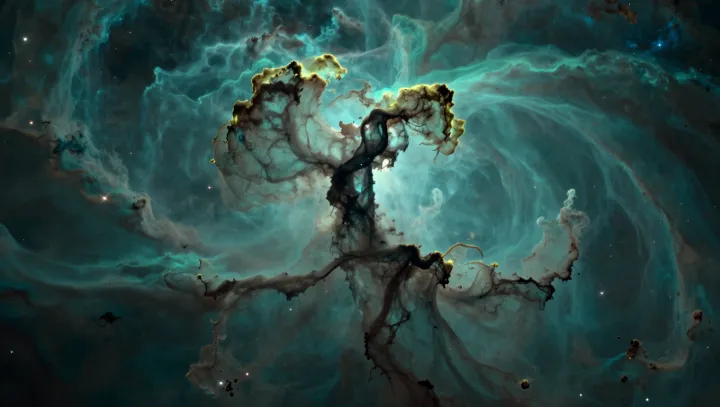

A rare astrophysical maser in an otherwise ordinary nebula revealed Doppler signatures of a hidden companion star that had evaded direct imaging.

So-called five-color porcelain depends on multilayer glaze interactions, optical interference and kiln chemistry, not a literal set of five pigments.

A thin veil of mountaintop snow exists only because tectonic plates collide, fold and uplift rock, turning deep crustal violence into high, cold platforms for ice and weather.