What Fruit Juice Really Does to Blood Sugar

Juicing removes fiber that slows glucose absorption, turning fruit into a rapid sugar load that spikes blood sugar and burdens insulin regulation.

Juicing removes fiber that slows glucose absorption, turning fruit into a rapid sugar load that spikes blood sugar and burdens insulin regulation.

Tidal friction between Earth and the Moon makes our planet’s rotation slow, lengthening the day while the Moon drifts outward by a few centimeters each century.

Captain America looks superhuman, but biomechanics and physiology show he is closer to a perfectly tuned Olympic decathlete than to a being that breaks human biological limits.

Modern navies model vast, modular fleets in software, but hydrodynamics, fuel logistics and human endurance sharply cap what can actually sail.

Viewed from Tokyo Skytree, Mount Fuji appears sharper in winter because colder, drier, denser air changes humidity, aerosol load and Rayleigh scattering, cleaning up the long sightline.

A children’s racing cartoon turns lap times and pit stops into a subtle guide to burnout, ego management, and graceful aging that most self‑help manuals miss.

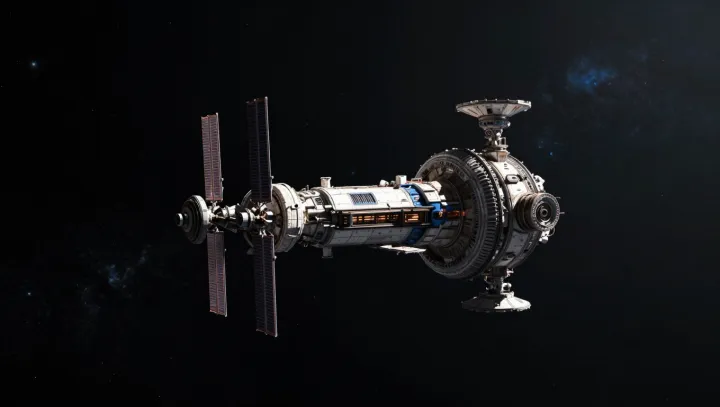

Space stations function as weightless laboratories where microgravity exposes hidden rules in fluid dynamics, biology and materials science, far beyond the idea of orbiting hotels.

A roadside bird that freezes with spread wings is not acting out a mythic death pose but a reflex called tonic immobility, driven by ancient neural circuits and stress chemistry.

Small, low cost parrots rival large talking species because their social cognition, vocal learning circuits, and routine proximity with humans create dense, low friction interactions that feel like real companionship.

Tea flavonoids can kill or slow cancer cells in controlled cell cultures, but metabolism, dose, and lifestyle noise dilute those effects in real life, so cancer protection is never guaranteed.

Olympic sailing teams exploit fluid dynamics, angle to the breeze and apparent wind to drive foils and sails so efficiently that boats can exceed true wind speed on specific courses.