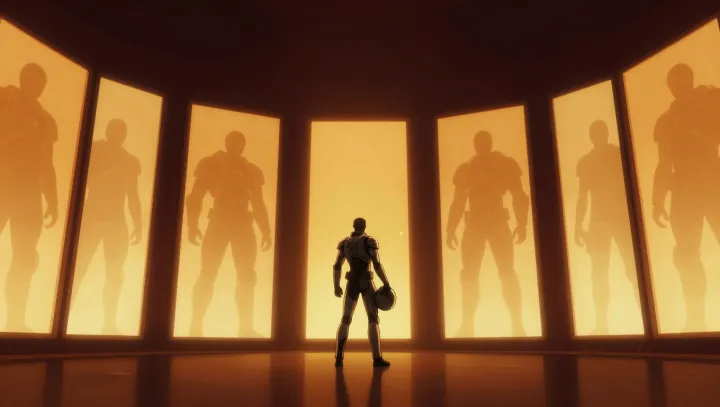

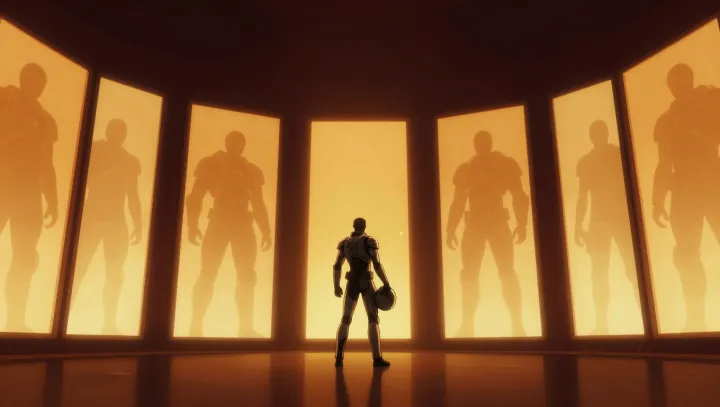

Iron Man’s Real Power Problem

Iron Man’s flight fantasy runs into hard physics: current batteries lack the energy density and power-to-weight ratio to sustain a man-sized flying exoskeleton.

Iron Man’s flight fantasy runs into hard physics: current batteries lack the energy density and power-to-weight ratio to sustain a man-sized flying exoskeleton.

A look at how small pressurized modules evolved into a precisely docked orbital megastructure using orbital mechanics, docking autonomy and international engineering standards.

Small, low cost parrots rival large talking species because their social cognition, vocal learning circuits, and routine proximity with humans create dense, low friction interactions that feel like real companionship.

A once-dismissed kids’ cartoon quietly mapped out facial recognition, algorithmic politics, and platform power long before white papers, revealing how pop culture can surface weak signals of future systems.

Honey shifted from ancient wound treatment to rigorously tested natural preservative, thanks to its low water activity, acidity, hydrogen peroxide and antimicrobial compounds.

Rabbits place their eyes on the sides of the head, gaining near panoramic vision while leaving a small frontal blind spot shaped by optics and neural wiring.

Invisible odors plug straight into the brain’s limbic system, bypassing slower visual pathways and giving scent a unique leverage to reignite vivid, emotionally loaded memories.

Modern anime studios invest heavy planning into static layouts, camera blocking and compositing, because coherent visual continuity and production efficiency now matter more than drawing every new frame.

Rural wealth is tilting toward data-driven farms, cold-chain logistics and e-commerce hubs, where margins scale with algorithms, networks and asset utilization rather than pure land yield.

Deserts combine extreme physical stress with tightly tuned adaptations in organisms and soils, creating ecosystems so fragile that a single tire track can disrupt them for decades.

A look at how Wat Chalong’s layout, filtered light, acoustic design, and ritual sound interact with physiology to reduce stress amid intricate Buddhist art.