How Rabbits Watch Almost Everything

Rabbits place their eyes on the sides of the head, gaining near panoramic vision while leaving a small frontal blind spot shaped by optics and neural wiring.

Rabbits place their eyes on the sides of the head, gaining near panoramic vision while leaving a small frontal blind spot shaped by optics and neural wiring.

Golf’s traditional solo format has branched into team structures like foursomes and four-ball, changing risk, strategy and psychology without altering the physics of any swing.

Rockets accelerate in space because hot exhaust is hurled backward, and conservation of momentum forces the rocket upward, even in a perfect vacuum.

Rural wealth is tilting toward data-driven farms, cold-chain logistics and e-commerce hubs, where margins scale with algorithms, networks and asset utilization rather than pure land yield.

From one clay body and shared kilns, blue-and-white porcelain and overglaze enamels split into two aesthetic dialects that still define how collectors read value and meaning in Chinese ceramics.

Wheat uses distinct gene networks for cold and drought tolerance, toggling molecular programs that rewire membranes, osmotic balance and growth to survive opposite climate extremes.

Tidal friction between Earth and the Moon makes our planet’s rotation slow, lengthening the day while the Moon drifts outward by a few centimeters each century.

Traditional New Year rules work because they target habit loops and neuroplasticity, rewiring reward pathways exactly when you feel tempted to rely on luck.

A steel ship floats in shallow water because its average density and displaced volume satisfy Archimedes’ principle, while a compact steel bolt exceeds water density and cannot generate enough buoyant force.

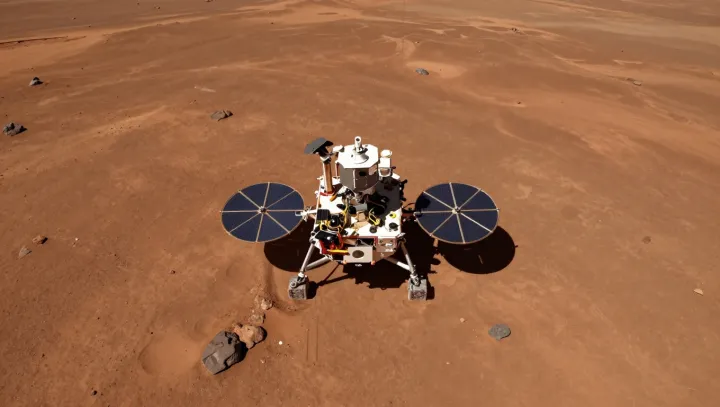

A stationary Mars rover built a multi-filter mosaic selfie to calibrate cameras, decode soil and ice composition, and refine climate models, turning vanity shots into hard planetary data.

Tidal friction between Earth and the Moon is steadily lengthening the day and pushing the Moon outward, revealing long term changes in Earth’s rotation.