Why Honey Soothes Kids’ Coughs But Not Babies

Honey coats an older child’s throat and modulates cough reflex better than many syrups, but the risk of infant botulism makes it unsafe for babies under one year old.

Honey coats an older child’s throat and modulates cough reflex better than many syrups, but the risk of infant botulism makes it unsafe for babies under one year old.

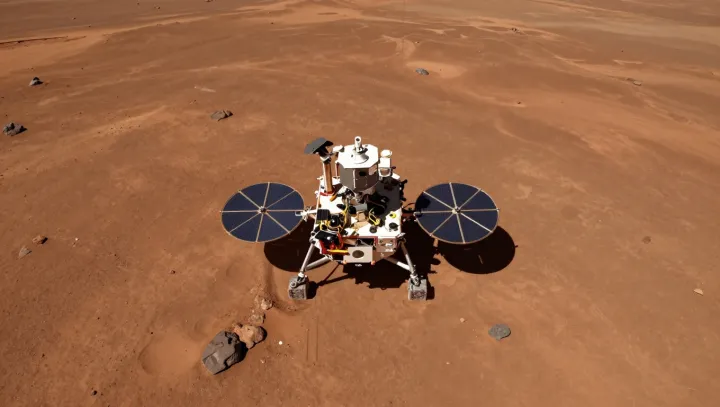

A stationary Mars rover built a multi-filter mosaic selfie to calibrate cameras, decode soil and ice composition, and refine climate models, turning vanity shots into hard planetary data.

Overwatering strips soil of air, triggers anaerobic microbes, and causes root rot in succulents that evolved for drought, turning life-giving water into a lethal stressor.

Many solemn masterpieces seem unintentionally comic once viewers decode the rigid visual grammar, social etiquette and symbolic constraints that originally signaled status and morality.

Two wool jackets diverge wildly in price when human hours, controlled supply chains and engineered scarcity turn fabric into a financial asset and a status signal.

Hand sketching remains central to car design because it compresses cognition, supports entropy-rich exploration, and shapes brand identity before 3D tools lock geometry.

Repetitive long-distance hiking reshapes spatial memory and risk circuits in the brain, building a more efficient internal map that improves route-finding and judgment under pressure.

Simple cartoon faces hijack high-level visual processing and social brain circuits, turning minimal lines into powerful emotional triggers.

Black holes are not perfectly black. Quantum field theory near the event horizon predicts Hawking radiation, which drains their mass as entropy and information flow outward until the object vanishes.

Whales are air-breathing mammals whose lungs, metabolism and evolutionary history force them to surface and exhale through a single modified nostril instead of using gills.

Audi intentionally offset elements of its four-ring logo so motion blur and human visual perception make it appear perfectly aligned at highway speeds.