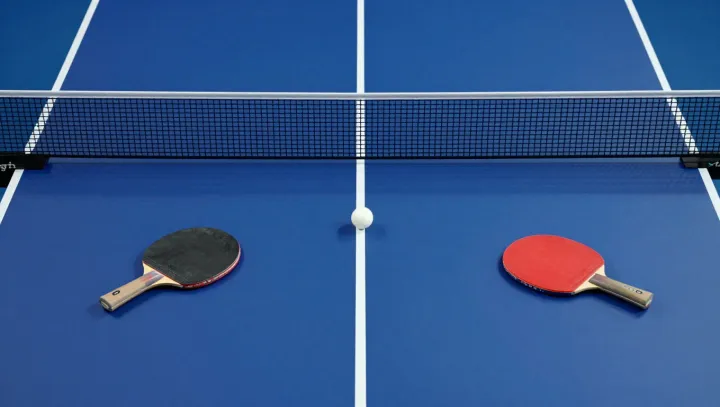

The Safer Table Tennis Ball That Barely Clears

A ball grazing only millimeters above the net exploits geometry, aerodynamics and spin dynamics, often making it safer and harder to attack than a faster, higher shot.

A ball grazing only millimeters above the net exploits geometry, aerodynamics and spin dynamics, often making it safer and harder to attack than a faster, higher shot.

Mount Kailash anchors the headwaters of four major Asian rivers not by a summit spring, but through its role as a watershed divide shaped by tectonics, glaciation and regional monsoon dynamics.

Iron Man’s flight fantasy runs into hard physics: current batteries lack the energy density and power-to-weight ratio to sustain a man-sized flying exoskeleton.

A club mocked as a fading commercial brand has turned its stagnant results into a live experiment in how narrative, identity and ritual can lock in global fan loyalty.

Minimalist looks with one neon accent feel high fashion because they reduce cognitive load, heighten contrast, and trigger reward circuits for efficient visual processing.

The Lamborghini Countach turned bad rear visibility and an extreme wedge profile into a high‑impact design language that reset supercar aerodynamics, ergonomics trade‑offs and brand psychology.

A powerful coastal typhoon can drench cities while at the same time reducing human heat stress by cutting solar radiation and limiting net heat gain at the surface.

A look at how Wat Chalong’s layout, filtered light, acoustic design, and ritual sound interact with physiology to reduce stress amid intricate Buddhist art.

Many “impossible” future city illustrations look fantastical yet quietly follow structural physics and urban‑planning logic more rigorously than mainstream sci‑fi cinema.

So-called five-color porcelain depends on multilayer glaze interactions, optical interference and kiln chemistry, not a literal set of five pigments.

Quiet lakeside settings reduce cognitive load and restore attention networks, often delivering deeper mental recovery than activity‑heavy wellness programs.