The Glacier That Moves While It Looks Still

Briksdalsbreen appears frozen from the trail, yet its ice deforms, fractures, and grinds rock, flowing downhill under gravity and reshaping the Norwegian valley.

Briksdalsbreen appears frozen from the trail, yet its ice deforms, fractures, and grinds rock, flowing downhill under gravity and reshaping the Norwegian valley.

Small, low cost parrots rival large talking species because their social cognition, vocal learning circuits, and routine proximity with humans create dense, low friction interactions that feel like real companionship.

The Lamborghini Countach turned bad rear visibility and an extreme wedge profile into a high‑impact design language that reset supercar aerodynamics, ergonomics trade‑offs and brand psychology.

Giant pandas have small, pale tails, but evolution favored their high‑contrast coat for signaling and snow‑rock camouflage, not for displaying a tail.

Chronic gender bias in childhood acts as a long-term neurobiological stressor, altering cortisol regulation and prefrontal-limbic connectivity in girls and leaving measurable traces in adult self-control and health.

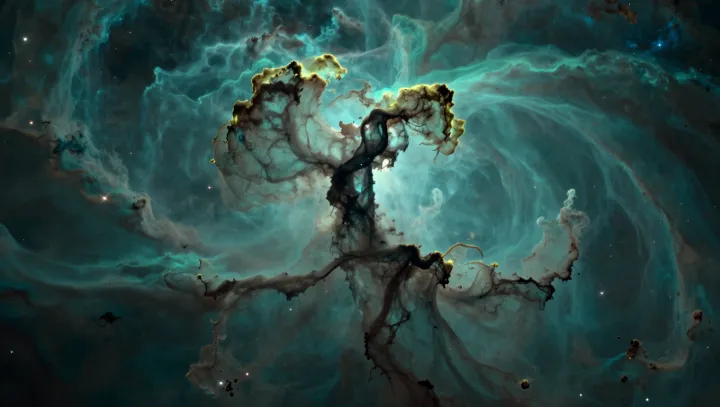

A rare astrophysical maser in an otherwise ordinary nebula revealed Doppler signatures of a hidden companion star that had evaded direct imaging.

Rockets accelerate in space because hot exhaust is hurled backward, and conservation of momentum forces the rocket upward, even in a perfect vacuum.

Astronauts train underwater because neutral buoyancy lets engineers and crews rehearse orbital weightlessness, refine procedures, and manage physiological limits before real missions.

From one clay body and shared kilns, blue-and-white porcelain and overglaze enamels split into two aesthetic dialects that still define how collectors read value and meaning in Chinese ceramics.

Meerkats in harsh deserts coordinate sentinels, hunters and babysitters without leaders, using simple rules, kin selection and constant vocal signalling to keep the whole group alive.

Juicing removes fiber that slows glucose absorption, turning fruit into a rapid sugar load that spikes blood sugar and burdens insulin regulation.