The Farm Girl Who Conducted a Rural Clock

The article explores how Winslow Homer’s painting of a farm girl with a dinner horn reveals a sound-based system of coordinating rural labor and social time before mechanical clocks and telecommunication.

The article explores how Winslow Homer’s painting of a farm girl with a dinner horn reveals a sound-based system of coordinating rural labor and social time before mechanical clocks and telecommunication.

Alps in Europe, Japan, New Zealand, and North America share a name because people reuse familiar labels for similar landforms, exposing a cognitive shortcut in global place-naming.

Juicing removes fiber that slows glucose absorption, turning fruit into a rapid sugar load that spikes blood sugar and burdens insulin regulation.

A single sweep along Tokyo’s commuter lines links five stops where local food culture, luxury shopping, and iconic cherry blossoms sit within walking distance of ordinary platforms.

The piece tracks the sneaker’s rise from industrial workwear to speculative luxury asset, powered by celebrity signaling, scarcity economics and platform resale dynamics.

Astronomers used orbital dynamics, chemical clues and population simulations to trace the first confirmed interstellar object back to the dense, chaotic environment near the Milky Way’s core, where ancient stars shape exotic planetary systems.

Galaxies rotate like cosmic hurricanes, yet stars orbit too fast to be held by visible matter alone, pointing to dark matter as the unseen gravitational framework.

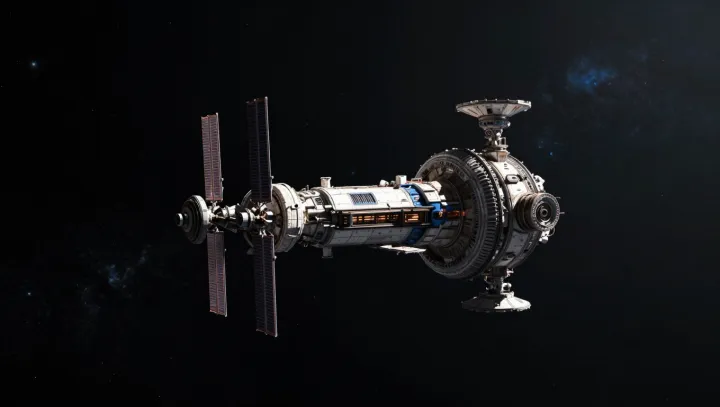

Space stations function as weightless laboratories where microgravity exposes hidden rules in fluid dynamics, biology and materials science, far beyond the idea of orbiting hotels.

Hand sketching remains central to car design because it compresses cognition, supports entropy-rich exploration, and shapes brand identity before 3D tools lock geometry.

Rewatching SpongeBob as an adult reveals how its absurd humor quietly trains a child’s brain to handle ambiguity, encode memories, and test social norms.

A roadside bird that freezes with spread wings is not acting out a mythic death pose but a reflex called tonic immobility, driven by ancient neural circuits and stress chemistry.