Rewatching SpongeBob With An Adult Brain

Rewatching SpongeBob as an adult reveals how its absurd humor quietly trains a child’s brain to handle ambiguity, encode memories, and test social norms.

Rewatching SpongeBob as an adult reveals how its absurd humor quietly trains a child’s brain to handle ambiguity, encode memories, and test social norms.

An Akhal‑Teke can legally cost more than a Ferrari because of extreme genetic rarity, metallic hair microstructure, and a tightly controlled desert‑bred performance bloodline economy.

A bone-inspired luxury jewelry collection uses anatomy, entropy and material science to turn fragile biology into a visual argument about evolution, permanence and metamorphosis.

Honey coats an older child’s throat and modulates cough reflex better than many syrups, but the risk of infant botulism makes it unsafe for babies under one year old.

Emerging feline research suggests grooming, litter-box use, and sleep locations may reveal stress, pain and immune shifts more reliably than food, toys or visible mood.

A dormant‑looking volcano continually feeds magma, gas and heat into a sealed system, raising pressure underground until rock fails and energy is released in a rapid, explosive eruption.

A club mocked as a fading commercial brand has turned its stagnant results into a live experiment in how narrative, identity and ritual can lock in global fan loyalty.

So-called five-color porcelain depends on multilayer glaze interactions, optical interference and kiln chemistry, not a literal set of five pigments.

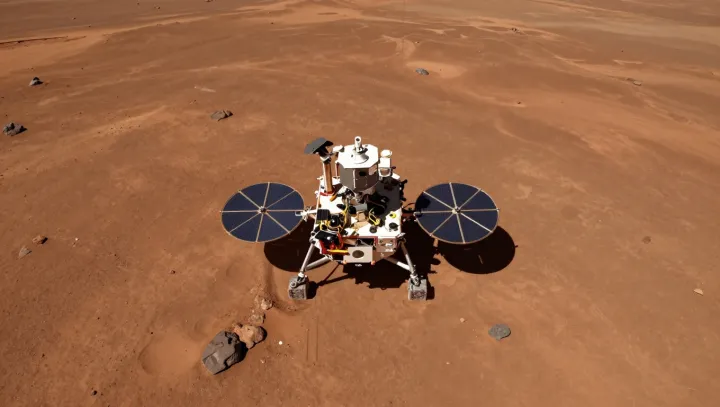

A stationary Mars rover built a multi-filter mosaic selfie to calibrate cameras, decode soil and ice composition, and refine climate models, turning vanity shots into hard planetary data.

Alps in Europe, Japan, New Zealand, and North America share a name because people reuse familiar labels for similar landforms, exposing a cognitive shortcut in global place-naming.

Tiny emoji work as fast semantic cues: they modulate reading speed, emotional valence and perceived politeness by hijacking prediction, attention and social norm circuits.