The Hidden Physics Behind Effortless Deep Threes

The most powerful three‑pointer emerges when the shot becomes a whole‑body kinetic chain, turning stored elastic energy and angular momentum into an almost effortless launch.

The most powerful three‑pointer emerges when the shot becomes a whole‑body kinetic chain, turning stored elastic energy and angular momentum into an almost effortless launch.

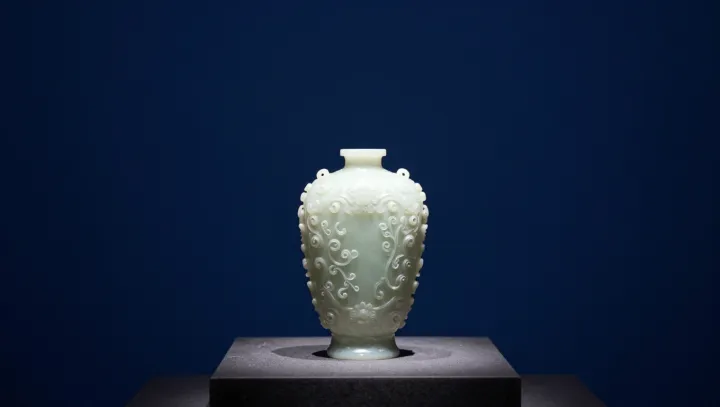

The winter‑blooming plum blossom rose to the top of Chinese floral rankings because its biology and timing matched ideals of moral resilience and cultured restraint.

Psychologists argue that accurately naming emotions calms the brain’s threat circuitry and activates problem‑solving networks, making emotional lows shorter and easier to navigate.

Even when the sea looks calm, small ripples act as a dynamic record of distant winds, tides and the combined gravitational pull of the Moon and Sun on Earth’s oceans.

The Lamborghini Countach turned bad rear visibility and an extreme wedge profile into a high‑impact design language that reset supercar aerodynamics, ergonomics trade‑offs and brand psychology.

Small, low cost parrots rival large talking species because their social cognition, vocal learning circuits, and routine proximity with humans create dense, low friction interactions that feel like real companionship.

Emotionally soft homes usually rest on tough conversations about boundaries, needs, and conflict, creating psychological safety through honesty rather than constant harmony.

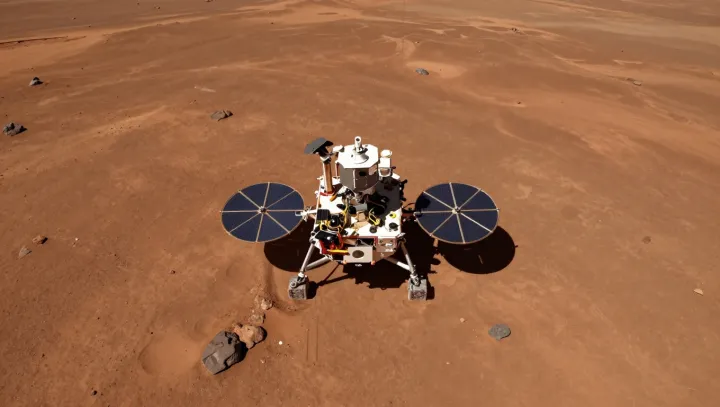

A stationary Mars rover built a multi-filter mosaic selfie to calibrate cameras, decode soil and ice composition, and refine climate models, turning vanity shots into hard planetary data.

Thunderstorms can launch upward lightning called gigantic jets and sprites, powered by electric fields that punch through the upper atmosphere toward space.

Astronomers use transit dips, stellar wobbles, and thermal spectra to infer exoplanet atmospheres so extreme that glass rain and global lava seas are now observational results, not fiction.

A short parasail behind a yacht can feel more mentally refreshing than long meditation because acute arousal hijacks attention, disrupts habitual rumination and recalibrates stress circuits.